What is the volume of a ball of dimension

and radius

? This ball is the following subset of

:

and we measure the volume using the standard Euclidean measure.

If you only need the answer for even dimensions, here’s an easy way to remember: define to be the sum of the volumes of balls of radius

over all of the even dimensions:

.

Remarkably, the formula for this function turns out to be . This is easy to remember since it’s the exponential of the volume (i.e. the area) of a disc. Then, you can read off the volumes

as the terms in the Taylor expansion of

. Explicitly:

A nice, and immediate, corollary is that the derivative of , with respect to the radius

, gives you the sum of the volumes of all of the odd-dimensional spheres:

By looking at the coefficients of the Taylor expansion, we can conclude that the volume of the unit sphere of dimension is

.

There’s a lot more to say about the volumes of balls and spheres, and if you’re interested, the Wikipedia page is a good place to start.

Okay, but why is the formula for true? And what’s special about even dimensions? That’s what I want to explain in this post.

In everything I’ve told you so far, there are really only two key facts from which everything follows. First, there is the formula for the area of a disc Second, there is the relationship

This says that the volume of a product of copies of a disc

is

times the volume of the corresponding ball. This fact is reminiscent of another interesting volume computation: the volume of an

-simplex

.

Computing the Volume of a Simplex

There are different realizations of the simplex, and they don’t all have the same volume. We will need the following version:

Here’s a picture in two dimensions:

In this picture, it’s quite easy to see that the two-dimensional simplex fills out exactly half of the square, and for this reason, its area is This fact can be easily generalized to all dimensions, giving the following formula:

Here is the argument: a point in the cube is a collection of numbers

which all lie between

and

. For almost all of these points (namely, those for which none of the coordinates

are equal to each other), there will be a unique permutation

that orders the coordinates

and therefore sends the point

into

. This implies that by applying permutations

the simplex

is transformed into a collection of

distinct simplices which completely fill out the cube. In other words, the cube

decomposes into a collection of

simplices, implying that

Just as for balls, we can package the volumes of the simplices of various dimensions into a single function

and from the above calculation, it follows that .

Comparing this volume of a simplex to the volume of an even-dimensional ball, we notice the following analogy:

The simplex is to the cube

(which is a product of

intervals), as the ball

is to the polydisc

(which is a product of

discs).

At least, this is true when considering volumes. What I want to explain in this post is that this analogy can be made precise. In fact, the volume of the even-dimensional ball can be derived from the volume of a simplex.

Before we continue, a simplification: since the volume of an -dimensional shape of ‘radius’

has the form

, the main interest lies in determining the coefficient

, which is the volume when

Hence, for the rest of the post I will simplify the formulas by setting

Tropicalization

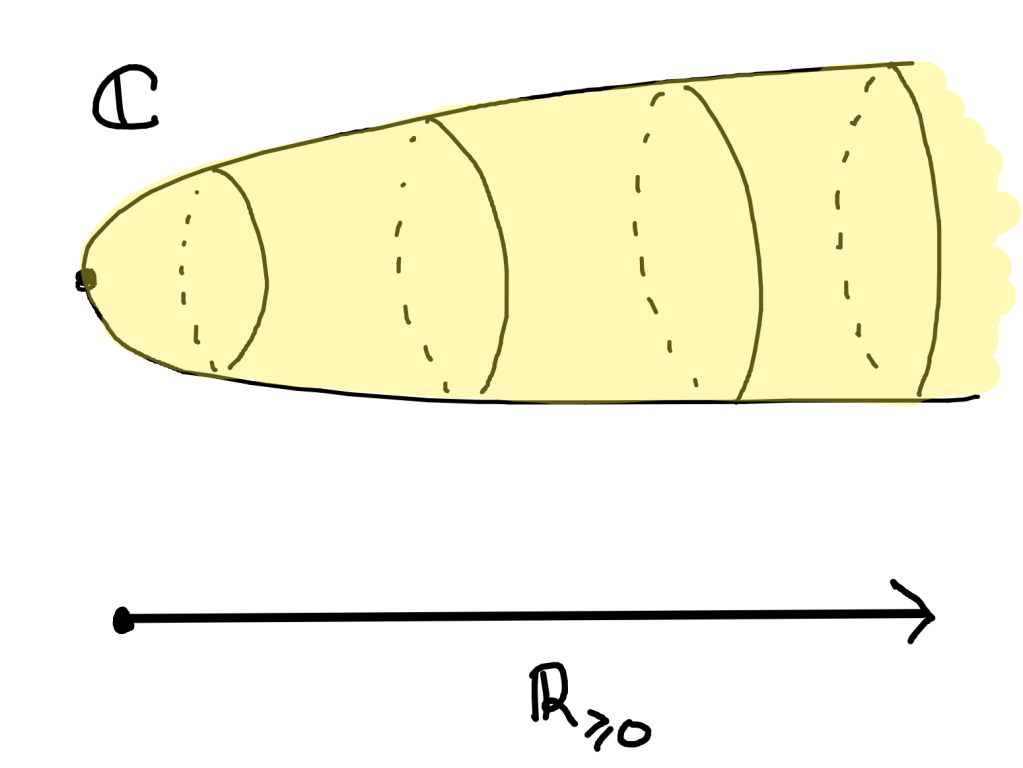

The key to the comparison between even-dimensional balls and simplices, and the answer to the question ‘why even-dimensional balls?’, is tropicalization, by which I mean the comparison between complex numbers and real numbers given by taking the radius squared:

You should picture this map in the following way:

Applying the tropicalization map to various subsets of produces subsets of

which are a sort of coarse-graining, in that the phase of the complex numbers have been forgotten.

In fact, this is not quite tropicalization. If you look in a paper, such as this one, you see that tropicalization involves taking the logarithm of the radius, , and then letting the base

go off to infinity. Using a finite value

, the images of subsets of

are what some people call amoebas.

In any case, the map above is what we need. The key fact is that it behaves well with respect to the Euclidean measures on

and

.

Lemma. The pushforward of the Euclidean volume form on

is the volume form

on

.

Indeed, writing the volume form on

in polar coordinates

gives

,

and integrating out the angle coordinate over the circle gives

, where

is the coordinate on

.

Given any subset which is invariant under rotation of phases, its volume can be computed as

,

where is the Euclidean volume of the image

Let’s see how this helps. First, the polydisc is given by the following subset of

:

Applying the tropicalization map produces the unit cube:

This implies that the volume of the polydisc is .

On the other hand, the -dimensional ball

is the following subset of

:

and tropicalization gives

This set is a simplex, but it isn’t quite the simplex we defined earlier. Here’s a picture of what you get in two dimensions:

You can see that this differs from the earlier picture of a simplex. In fact, the two simplices are related by a simple change of coordinates. Define

for . You should convince yourself that a point

lies in

if and only if the corresponding point

lies in

. But now observe that the linear transformation that produces the change of coordinates is a shear transformation. Indeed, it is given by the following matrix

whose determinant is easily seen to be . Therefore, the change of coordinates is volume-preserving and we see that

Combined with the previous facts, we conclude that

We have derived the volume of even-dimensional balls from the volume of simplices!

One thought on “The Volume of an Even Dimensional Ball”